Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS | More

Mind the Gap: can the study of art in a museum context help young students with their own reading and then creative writing?

Hello, my name is Rebecca Lefroy. I teach 7th, 8th and 9th grade at Lexington Christian Academy and am going to be talking about some research that I conducted in my previous school, in part for my Masters in Education.

Although, as you can probably tell from my accent, I’m British, I was fortunate enough to actually do quite a lot of my growing up in Brussels and so completed the IB (International Baccalaureate) at an international school there. My experience of the IB was hugely positive; I thrived on the creative, holistic and interdisciplinary approach to teaching the arts. I was therefore rather surprised when I started my job as an English teacher in the UK and discovered that there are distinct gaps between the arts – we teach in different buildings; have completely distinct curriculums; and the subject names sit inside closed boxes on students’ timetables. I asked myself: why the gap?

My interpretive case study therefore arose from two main perceived problems with our secondary English teaching:

- There seems to be a superficial gap between the arts subjects in secondary schools;

- Younger students tend to be taught a “checklist approach” to reading and writing rather than encouraged to view a text in a holistic way, exploring more abstract concepts.

I wondered whether some of the more abstract concepts which younger students so struggle to grasp – for instance, perspective, symbolism and style- be taught through some other, perhaps more accessible, art form – such as art in an art museum? And could what is learned then be transferred back to the English classroom?

I found Eilean Hooper-Greenhill’s (1999) approach to museum learning compelling – “the audience is always ‘active’, whether or not museums recognise this”. Furthermore, I was inspired by Cremin and Myhill’s (2012) argument that teachers should avoid formulaic recommendations when looking at students’ creative writing and instead see writing as a design process which encompasses both word and image. Similarly, Barrs and Cork (2001) take a more holistic view of creative writing and suggest that exposure to high quality literature can help students develop a wider repertoire of styles and a stronger sense of voice. Thus, I wanted to see whether learning about abstract concepts through art in an “active” environment as well as exposing students to high-quality literature that “plays” with design could push them in their own reading and writing.

The Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, UK was an excellent place to carry out the basis of my research and provided a very positive learning environment for the students. It’s a very grand building set right in the middle of the Cambridge colleges and they have a very extensive educational program. So, one afternoon, with about 20 grade 6 students in toe, we packed our bags and headed to the museum. We spent about 2 hours in the museum and through engaging, interactive activities, we explored how artists can use perspective, symbolism and style in their work and what effect this has on the viewer. For our work on perspective, we used Alfred Elnore’s On the Brink; for symbolism, Salvator Rosa’s L’Umana Fragilita (Human Frailty); and for style, Monet’s Springtime.

Compared to being in an English classroom, the students were much more willing to share their ideas, admit mistakes and take risks in the art museum. Interestingly, they also had more confidence in interpreting art for themselves than they did a written text in an English classroom. Through follow-up interviews, I found that, for some, this was because they found art an easier form to analyse because of the framing of the piece – “it’s all there in front of us” one interviewee told me – and partly because they felt more empowered to express their own interpretations of the piece in an open art museum space without tables, chairs, a whiteboard, and the implicit authority structure which inevitably exists.

In some cases, several of these positive learning behaviours and developed critical skills were then transferred back to the classroom when we came to look at narrative perspective, style and symbolism in written texts. Students were generally better able to understand that a written text has an author behind it after looking at how an artist makes deliberate decisions. This meant that, for some, their reading analysis demonstrated more confidence and insight.

But the most progress was shown in the students’ own creative writing. After the museum visit, we reflected on how the artists had deliberately “designed” the paintings and then looked at some graphic novels, most notably Shaun Tan’s books, and how they play with design and text. In their final creative writing piece, the students made remarkable progress, making really sophisticated decisions in perspective, style and symbolism. Twelve of the students scored higher than expected, some quite dramatically so. The interviews suggested that this was because the students felt more willing to take risks in the classroom since the museum visit and so were experimenting with art and text for themselves. Furthermore, some had discovered for themselves that writing can be seen as a holistic design process and doesn’t have to be a set of checklist boxes to fulfill.

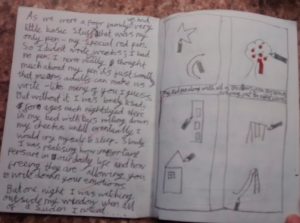

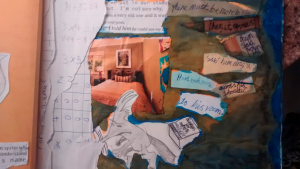

I’ve included images from two students’ work. You can see a scrapbook like image in one. In his commentary, the student wrote “I made it look like it was an old geography book and I also made it clear the narrator had ripped the pages out…because Bob, at the start, didn’t know that the book would turn out to be an actual book, it was just a project for him.” The second image shows one student’s story of a red pen that comes alive. Half-way through the book, it comes alive in the text too and interferes with the drawings! Both students are using perspective and symbolism in very clever ways, playing with reader interaction and perception.

This research project encouraged me to take a step back and ask myself what it is that I really want to teach my students about reading and writing. I know I certainly want to avoid slipping into simplistic transmission of technical features; instead, I want to help my students consider the design and constructed nature of a text. I want to see them discover that the richness that can be found in paintings is right there in literature too. A picture may tell a thousand words, but a thousand words paint a picture. And, certainly for this research project, this approach seemed to increase rather than deflate their attainment levels.

Why the gap? I’m not sure. Why not encourage an English class to visit an art museum or a Music class to welcome a visiting author? If we want to teach our arts subjects in a holistic, coherent way, surely we should find our fundamental common ground and use this to engage a whole variety of learners.

If you would like to read more about this research, you can find my published paper in Volume 52 Issue 2 of the research journal, English in Education.

Rebecca Lefroy